Starting Year 1920

Olive Ethel Utting

Olive in 1925

Olive arrived in Gateshead in 1921 and started Gateshead Secondary School in 2nd year. Her father was Arthur William Utting, the United Methodist minister at Amen Corner, Durham Road Bensham Road, and Sheriff Hill, which had a congregation of miners from Wrekenton. Mother was Florence Emma née Gaze. Olive gives a full account of her school days below After leaving school she got a degree in History from Durham.

Source http://www.picturesofgateshead.co.uk/postcards_gateshead1/opcg9w.jpg

She married Robert Pattison of Gateshead, who took the Hawthorn Leslie apprenticeship route to Imperial College. He was in the same congregation, though they both later became Quakers.They then travelled the world with Robert setting up technical education in developing countries: Trinidad, the Gold Coast (Ghana), and after his retirement from King's College London, Malawi. They have a daughter, Meg, a son Ian and countless grandchildren and great grandchildren

Olive 99 years old

Olive took up her first love by becoming GGSM (Graduate of the Guildhall School of Music). She taught History in school, and then Music, both in school and after her retirement, privately. She stopped for a bit in her late nineties after a health scare, but she's taken back some pupils, and she still plays in concerts locally.

This is Olive at her 100th birthday party viewing this website. Olive had written the piece about her life at Gateshead Secondary School and her daughter wanted to have it published in some way. We were delighted to oblige

****************************

These pupil's names have been supplied by Olive.E.Utting (later Pattison). As she is recalling her 1st Year 6th year, which was shared with 2nd year 6th, some of these pupils may belong to Starting Year 1919

Hugo Tyerman

John Charlton

Philip Gott

Reuben Dunn

Harry Hewitt

Bruce Pattison

Edith Bell

Annie Neale

Martha Rumsey

Peggy Bradshaw

***************************************************

Olive E. Utting writes

"Gateshead Secondary School

As I had been attending a grammar school in London (Haberdashers’ Aske’s Hatcham), there was no difficulty in arranging a transfer to Gateshead Secondary School. With some trepidation I entered the gates of the rather handsome ivy-covered red brick building with the Tower at one end, and followed the stream of chattering girls into an insanitary looking cloakroom with one old-fashioned roller towel. A bell rang and we made our way to the hall where we sang,

Lord behold us with thy blessing

Once again assembled here.

The staff, in academic gowns sat facing us on a new War Memorial stage of light unpolished oak .(It was Sept 1921, the WWI War Memorial was indeed brand new)— flanked by Honours Boards. -

The Head (Mr Walton) read the lesson from a handsome lectern and then read out the class lists I was assigned to 2B as if had been in 1B at Aske’s. There, it was merely a numerical division, not based on merit.

The class room was upstairs on the front overlooking Durham Road, and once there, we were imprisoned at our two-seater rather cramped desks until break. There was no free milk in those days. I suppose I might have felt hungry, but do not recollect it. We came home for lunch, skirting the perimeter of the school field, then past the Drill Hall and the old farm across Whitehall Road to Ashgrove Terrace. We consumed a substantial lunch, and returned for afternoon school heavier and drowsy.

My old gym frock was suitable with the addition of a school tie, girdle, and cloth side-peaked cap with the school monogram on the front. It was strange to be in a co-ed school again. I quickly made friends with several of the Tyneside girls who hospitably invited me to their homes for tea and included me on Form picnics. We were in the 12–13 age group but arranged these outings without adult supervision, packing our own “bait” or sandwiches and travelling incredible distances unchaperoned.

The first outing was by electric train from Newcastle Central to Tynemouth, where, on our own, we visited the Priory, then had a picnic tea and a paddle on the beach.

I have a photograph of the occasion. Boys were just not considered on these outings; in fact although they were educated with us, they sat in a separate block and we ignored one another — at this stage. At Fifth Form level when we put on plays together we began to show interest, but there were few “steady” affairs before the Sixth Form. Other activities centred round school Christmas parties. We were all expected to be able to dance — ball-room dancing — and a band was hired. As I came from a parson’s family I had never learned, and was embarrassed when invited to waltz or quickstep. I was shy and clumsy at it and invariably found I was steering my partner contrary to the general stream. A boy was expected to ask a girl to take her in to supper. I dreaded this indignity of waiting to be asked, but usually some unfortunate boy was directed by a member of Staff to pop the question. I had not noticed this Tyneside passion for ballroom dancing in our London suburbs — nor had I come across the “clicking” of couples.

The road at the top of Saltwell Park was the scene of great activity at nights when gangs of boys and girls moving in opposite direction would bump into one other and after some rough banter, pair off and disappear into the groves of the Park. My parents frowned on this promiscuity, although there was more horse-play than sex.

Saltwell Park, Gateshead

We had a wide curriculum: English was my favourite subject, especially poetry. Robert Armstrong introduced me to Extracts from Tennyson’s Morte d’Arthur and I chanted “So all day long the noise of battle rolled” — and “Blow, bugle, blow — let the wild cataracts leap up in glory!” — but most impressive of all was the extract from Wordsworth’s Ode on the Intimations of Immortality in Early Childhood: “We hissed along the polished ice in games confederate”. Shelley’s “Swiftly walk oer the western wave, Spirit of Light, But of the dark and misty cave, Where all day long thou wovest dreams Swift be thy flight.” Long portions of Hiawatha, “By the shores of Gitchie Gumee …” — and of course, the Border Ballads so relevant to this Tyneside setting.

I realise now that we were very well taught in an academic sense. The pupils, most of them working class to lower middle class, were hand picked in the “A” stream, as there were only 30 scholarships per year in a population of 30,000(?) We were given masses of homework which we never questioned. Lessons were thorough and inspiring, and the urge to study was engendered both by home influences — masses of books, an erudite studious parson father and a literary drama-loving mother — and the knowledge that if we were to proceed to University it was based on our showing in Matriculation and Higher School Certificate. There were twice-yearly exams in all subjects and Report Books were issued. Very sensibly there was no student positioning. We were graded: 66% 1st Class, 50–65 2nd Class; 40–50 3rd; under that, 4th. I have since tried in many schools, as a teacher, to introduce this grading system which eliminates personal competition and the ridiculous state of ten people all with 70 coming first, and the next with 69.5 coming 11th. The Report Book contained the whole of one’s academic and social record, with a final report for a testimonial for a job or college. It had to be signed by the parent and returned on the first day of the new term. The report books were kept in form order in the stock room.

Games were compulsory and there were extensive playing fields attached to the buildings: hockey in winter (which I dreaded as I feared for my glasses), tennis on grass courts in the halcyon summer days — foursomes. Tennis was the only game in which I excelled and won a place in the school team.

French was taught grammatically, not by the direct method, so that I could read and write fluently, but conversation was not stressed until the Fifth Form when we received special coaching for Matric. Oral. There were no tapes, although Daddy Morgan, our Music-cum-Geography master did teach us a French song of some length: “Dites la jeune belle, où voulez vous aller? La voile ouvre son aile, La brise va souffler …”

Singing lessons were taken by Daddy Morgan as a communal effort, I suspect to give the rest of the staff a break. We sang “A regular Royal Queen” (Gilbert and Sullivan) with great gusto and the two florid Henry Bishop old Victorian songs “Bid me discourse I will enchant thine ear, or like a fairy trip it on the green”. Daddy Morgan was short, rubicund with gold-rimmed glasses and white hair and bristling moustache. In addition to introducing us to The National Song Book, much of Purcell — “Come unto these Yellow Sands” — Purcell’s King Arthur, Handel’s “Where’er You Walk” — he was the Singing adjudicator with the Gateshead Musical Festival which was held in the Town Hall.

[OEP digresses into her musical interests and experience, which also involved the United Methodist Church of which her father was the minister.]

My singing prowess took me out with Mr Adams and The Band of Hope on week-nights, when all young and innocent we were taken into the public houses on High Street and lower West Street to sing hymns in the public bars

How at that tender age we gained admission is a puzzle to me now, but sing we did and were well received by the regulars.

I was appalled at the poverty we saw in the grim alleyways off High Street and was more than ever determined to be a missionary.

In recounting my musical experiences I have digressed from Gateshead Secondary School, its teachers and pursuits.

“Daddy” Morgan also taught us Geography. We copied pages of detailed maps for homework and memorised both physical and political geography. I delighted in neat map-work and still have my notebook with its miniscule printing and précis. We learnt map reading and contour planning.

I studied Botany for one year with Mr Young who really knew his stuff. We classified flowers and made artistic drawings of parts of bulbs, corms, rhizomes, root systems, types of leaves, kinds of trees, flower patterns and orders: cruciferae, leguminosiae, compositae, etc — each with its appropriate cross-sectional diagram. We tied covers over leaves to prove the presence of chlorophyll when light was present. We cross-pollinated plants, germinated peas and beans between damp blotting paper in jars, and made a collection of wild flowers. This year was all too brief.

Coupled with this, was a year of Physics and Chemistry, supervised by the indefatigable Mr Cheesewright, a master with saturnine features, a dome of a head with black hair, and a fierce expression which could break into a rare smile behind his moustachios. I was terrified of him at first, especially when he came across my fumbling efforts at setting up an experiment: “Are you afraid of a Bunsen Burner?” he yelled — then kindly lit it for me, and showed me how to use a pipette without acquiring a mouthful of whatever substance we were testing for its alkalinity or acidity, be it urine or sulphuretted hydrogen. He demonstrated the principle of Archimedes, showed us pink litmus paper turning blue, and that a pound of feathers was no lighter than a pound of lead.

On Sundays he was seen in a very different role, walking down Durham Road with his little prim Edwardian wife, to the Congregational Church on Amen Corner. Of him was quoted “Behind a frowning providence he hides a smiling face”.

The art room was presided over by Mr Rowell, a big, fair, heavy man who took his duties seriously by teaching us the rules of perspective, plant-drawing in pencil, and figure drawing. We made innumerable designs using geranium plants. I do not remember any imaginative art. It was all very controlled.

My bête noire was the Needlework teacher, the elderly Miss Robinson with her flaxen false hair secured to her head by a velvet band tied low round her brow. She was thin, yellow, and stooped. I thought she had T.B. Homework was excessive. We did not use machines but were well instructed in all facets of patch making — calico, flannel, cotton — mending of hedge tears, gathering of gathers into a band, pleating plackets, button-holes, blanket-stitching, joining of seams, and simple embroidery. For our School Certificate we had to make a nightdress in fine white madapolen — yards of it, gathered, stroked, and set into a yoke with scalloped neck and sleeves. The hand sewing was exquisite and iniquitously eye ruining. Years after I was married, I chopped it down into two nightgowns for my daughter, aged 8.

Miss Robinson and I did not get on very well. I resented the time spent on the wretched specimens when there were so many other exciting subjects waiting. I finally rebelled and found myself in the Head Master’s study for refusing to do the required homework. When he gathered the extent of the tasks set he realised that right was on my side. Never again was needlework homework so excessive and Miss Robinson became gentler to me in her manner. She died shortly afterwards of pernicious anaemia, poor soul. I suppose I really owe more to her than to any other teacher, for to this day I can make and mend. In my School Certificate exam we had to construct a pattern for knickers of vast proportions. They were gathered into a band at the top, and buttoned by a side gusset opening. I saw her pleadingly looking at me and afterward she told me that I had not cut the opening dividing the top front from the top back, i.e. there was no way in. It didn’t seem to matter, for by a miracle I passed with credit.

By the time I reached the Fifth Form, my brother Frank had gone to Armstrong College, Newcastle, then affiliated to the University of Durham. He was reading History and some of his enthusiasm rubbed off on me. I worked enormously hard at History for School Certificate, memorising maps of the Partition of Poland and Colonial possessions after the various wars of conquest.

.

Our History Mistress, Miss Hollis, was an extremely erudite and genteel lady who was supposed to have lost her fiancé in the 1914–18 war. She was distinguished-looking, with greying fluffy hair, rather prominent features and a monotonous voice. With her we read our way in the Sixth Form, through Marriott’s England under the Hanoverians; Trevelyan’s Nineteenth-Century History, and England under the Tudors and Stuarts, and Lyall’s British Dominion in India. I made copious notes and did vast quantities of extra reading.

Concurrently Mr. Heppell, an English scholar of some repute who edited editions of Shakespeare for Dent, was taking us through our Higher School Certificate English reading. Under his guidance I digested most of Palgrave’s Golden Treasury in the Fifth Form, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and The Tempest, then selections from the longer narrative poems in the Sixth — Wordsworth’s Michael, Arnold’s Sohrab and Rustum, Browning’s My Last Duchess, Fra Lippo Lippi, The Patriot, and others; Chaucer’s Prologue, The Knight of the Burning Pestle by Beaumont and Fletcher, Julius Caesar, The Winter’s Tale, As You Like It, and Henry V; Marlowe’s Faustus and Edward II. We wrote weekly essays on “Probability is the Guide of Life”, “It is better to travel hopefully than to arrive” … I was still undecided what to read at University, but supposed it would be History, like my brother.

French and Latin could have been a possibility but our family finances could not allow of foreign travel and without residence in the country, fluent speech would be impossible. However I read much Victor Hugo: Quatre Vingt Treize; Poèmes — “Moise”, “La mort du Loup”; Les Miserables, Balzac’s Eugenie Grandet; de Musset’s Poèmes, Molière’s Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme; and today can still read fluently.

Latin took me through Caesar’s Gallic Wars, Tacitus’ Agricola and Horace’s Satires, together with an outline of Roman history and culture, and Virgil’s Aeneid Books III and VI.

All my studying was done at an old wash hand stand up in the attic of No 3 Ashgrove Terrace where we lived. I spent incredibly long periods up there swotting in an unheated, empty dusty room. I had to have complete silence in .

No. 3 Ashgrove Tce

which to concentrate. Luckily we were all studying in different rooms and there was no distracting wireless or television. When we felt stale, we would dash through Saltwell Park or bat a ball up and down our narrow back yard, or have a sing song.

I cannot remember finding all this study a hardship. I was naturally studious and enjoyed acquiring knowledge in the only medium open to us — the reading of text books and newspapers. We studied current events avidly, both at home and at school, carefully scanning the newspapers and keeping clippings for the news board. What excitement there was at the opening of Tutankhamen’s tomb! As each new treasure was brought to light it was listed and the subsequent tragic death of Lord Carnavon from a rare disease contracted while on the dig filled the nation with horror and apprehension. Was it the bubonic plague — the king’s evil — small pox?

I took a major part in two school plays and earned the reputation of being a Mrs Siddons.

I was Lady Hardcastle in She Stoops to Conquer, with Tony Hewitt as Tony Lumpkin and I played Maria in Twelfth Night, to Bruce Pattison’s Malvolio. We had great fun in rehearsal. Miss Hollis did all the production and costumes, and we went to her flat to be fitted. It was peculiar in that there was not a single mirror in the place. We hired the costumes from a theatrical agency.

The Prefects’ room was in the tower. Above it was an unboarded area where stage props were balanced. Rimer, a prefect, climbed into this loft and trod heavily between the rafters. There was a rending sound as a pair of legs suddenly shot through the ceiling.

(This is almost certainly Eric Rimer, the teacher who was also a former pupil)

It seems appropriate here to mention some of my schoolfellows. We had two years in the Sixth but both section were taught together — a stimulating arrangement since we were pitting our wits against folks such as Donald Tyerman, who became Editor of the Economist; Bruce Pattison, later Professor of English as a foreign language at London University; Harry Hewitt who joined the Society of Jesus at Mirfield College. Others were Reuben Dunn, a fair-haired athlete and footballer; Philip Gott who was forcibly shaved by the Sixth Form boys; John Charlton, an earnest tall dark, sharp featured bespectacled youth with a great sense of humour who wanted to be a doctor; and if there were others I cannot recall them.

Of the girls Edith Bell, tall, bony, with straight fine fair hair tied in two plaits, rimless glasses, and sharp features, went on to Armstrong to study Botany and Zoology and probably became a Science teacher. She lived in a council house on Sheriff Hill with a mother and brothers who were equally tall and bony.

Annie Neale, a small round mousy retroussé-nosed girl of about my height — 4’11” — lived in my direction so I had to listen to her tales of conquest of the opposite sex …. She landed up doing a General Arts degree at St Hild’s Durham. We played in tennis matches together and served teas to visiting games’ teams …

My other friend was one for whom we were all sorry — Martha Rumsey. She [wore] a pair of ugly steel-rimmed spectacles with the thickest lenses I have ever seen. She had a creamy skin which goes with tawny hair which she wore parted very much to one side and fluffed upon top — back-combed we should call it today. She kept it in place with a black velvet band … She usually wore velvet dresses and was grateful for companionship, so she came everywhere with us, and because she was so blind we supplemented her lesson notes, and retailed any details she had not grasped. She was avid over Latin, and a wizard at construing unseens. Alas — she passed her Higher School Certificate but had to enter a School for the Blind where she learnt Braille and became a teacher of the Blind. I met her some years later, still affectionate and grateful for kindness. Martha had one sister younger than herself and a mother and father who were decidedly odd … Her father had an allotment below Saltwell Park and there he created a fantasy world of waterways, windmills that turned mechanically and gnomes and scarecrows that leered. Every so often he would cackle in some West Country tongue, “He be larfin’ at oi. Look out he doan’t git yew.” He then executed a droll caper among the cabbages, rubbed the side of his nose, winked and bolted into a garden shed from which he would not emerge until after we had gone. His conduct so alarmed Martha’s visitors that our visits to the allotment were brief. One imagined that here truly there was something nasty in the woodshed.

Although there were very few boy-girl “steadies”, there were a few. Tyerman was sweet on Peggy Bradshaw, a lovely dark-eyed fine-featured beautiful girl with a sense of mischief. Tyerman was lame and walked with the aid of two sticks. He had contracted polio as a child in the Gold Coast. His mother was a widow and a teacher. Tyerman was exceedingly handsome with straight regular features, wavy hair and dark gypsy eyes, and flashing teeth. He played a wonderful game of cricket and played for the school team, somebody doing the runs for him while he hit the boundaries. He was editor of the school magazine and was school captain of the boys, while I was captain of the girls. As I am not a sporting type, I realised that my appointment was for dramatic talent and for my academic distinctions in School Certificate. By sheer hard work I knocked up distinctions in History, French, and Latin; special credits in English and Geography, and credits in Art and Needlework and Maths. I must have appeared an insufferable brat, but the fact is I loved book learning and I was set on going to University.

Just about this time a new preparation appeared on the market — a tonic called Phospherine. During my exams I took a dose before each session and it made my memory and reasoning unnaturally bright. Towards the end of the three week stint I became very wobbly and nearly passed out.

I tried Phospherine during Higher School Cert, but it did not seem to work again, but this was owing to a calamity which befell in my exam term in 1926.

[The calamity was catching scarlet fever from her younger sister and following her into Sheriff Hill Isolation Hospital, from which she only emerged three weeks before the Higher School Certificate, without having had any text books in the hospital to revise from. Besides this, three smallpox victims were admitted to the ward, and everyone was forcibly vaccinated: hers took very badly. As a result she did not do as well as she had hoped and expected, but was still accepted for Armstrong College.]

Meanwhile my sister Muriel was also growing up … She joined me at Gateshead Secondary School in my final year in the Sixth, as a First Year.

Her writing was woefully untidy and Mr Young, Botany, appealed to me to take her in hand. This was quite impossible. Muriel always wrote her homework lying flat on her stomach on the floor with her bottle of ink beside her. Often it was knocked over and I discovered that after blotting up what I could, a mixture of milk and salt brought out most of the rest.

It was ever thus with teenage girls

Luckily manse carpets were always patterned in red, blue, and black, so ink was not too conspicuous.

My only other recollections of school were of Mr Heppell, [English] sitting down beside the girls to correct their work as they proceeded (I think his legs were tired and he was glad to sit down — a charitable view not shared by the boy pupils); and of our French master Mr Harbron who used to fall in love with senior girl pupils. He became engaged to one but never married ...

Finally, Mr Miller tried his best to teach me Maths. I was good at Arithmetic, but at Haberdashers’ Aske’s we did not begin Algebra or Geometry until the 2nd year, so I missed the foundations of both these subjects and never caught up. I once achieved minus 20 in an algebra exam and it was a great worry to me as to matriculate one had to pass with credit in School Certificate in at least six subjects at one go, of which Maths and English were compulsory. If I failed in Maths, bang would go my chances of a university career. How the problem was resolved deserves a chapter to itself.

This then was my school life: extremely academic, practical, artistic, dramatic, musical. Games were compulsory; school hats, blouses, ties and gym slips ditto, but overcoats were of our own choice. We had no swimming bath, no films: but Sir Frank Benson gave us one of many farewell recitals of Shakespeare, and we were visited by Ben Greet’s Shakespearian Company. I shall never forget Frank Benson as Henry V, shouting “Bring me meinarmer (mine armour)”.

The talkies were ousting silent films and Tyerman and his current girl friend saw them all at the Coatsworth Road cinema.

Coatsworth Road, Gateshead

As children of the manse we were unable to see films: (a) they were morally undesirable; (b) we had no money. Wireless was in its infancy and there was much building of home-made sets and talk of cat’s whiskers. We listened in through head-phones at the homes of our friends — news items and classical music, mostly Mendelssohn.

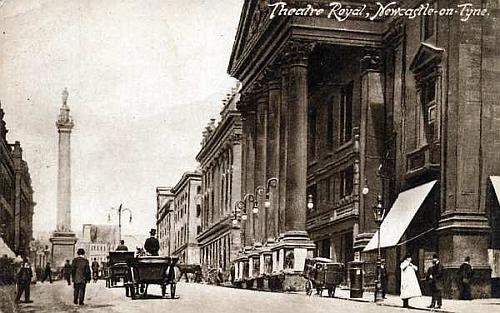

In 1924, as a special treat father took us to the Newcastle Theatre Royal to see a revival of Gay’s Beggar’s Opera. The Gallery was crammed, mostly with clergy and their offspring, who somehow wrongly conjectured that it was suitable for adolescents. Their faces were a study in consternation as Macheath’s love life was laid bare. I noticed however that for weeks afterward snatches of “How Happy Could I be with either”, “Were I laid on Greenland’s Coast”, and “Youth’s the Season made for Joys” were being sung by father as he prepared his sermons. Another pleasure-starved cleric openly admitted that he had had himself elected to the Watch Committee so that he could spend his Monday mornings in the cinema watching doubtful films. He was rigorous in his exclusion of the morally questionable. "

* * * * * *